4 Searching the Literature

If you’ve ever felt overwhelmed by the prospect of searching the literature, you’re in good company. The sheer volume of published research is staggering. PubMed alone contains over 36 million citations. Google Scholar indexes hundreds of millions of documents. And that’s just the stuff that’s been published in English in indexed journals—we haven’t even talked about grey literature, reports from ministries of health, or the dissertation gathering dust on a shelf in Nairobi that contains exactly the information you need.

Here’s what I want you to understand from the outset: searching the literature is not a mechanical task you complete and check off a list. It’s a thinking process. The way you search reflects what you know, what you think you know, and what you don’t yet realize you need to know.

“The literature” isn’t a single thing. It’s a sprawling, constantly growing ecosystem of peer-reviewed journals, preprints, reports, theses, conference proceedings, and policy documents scattered across databases, repositories, and dusty filing cabinets around the world.

This chapter will equip you with the skills to search effectively, whether you’re doing a quick scan to orient yourself or conducting a rigorous systematic review. We’ll talk about when to use which approach, how to build search strategies that actually work, where to find the evidence that doesn’t show up in PubMed, and how to avoid the traps that catch unwary researchers—from confirmation bias to predatory journals.

4.1 Choose Your Review Type

Before you type anything into a search box, you need to answer a fundamental question: What kind of review are you actually doing?

This matters more than you might think. The expectations for rigor, the time required, and the methods you’ll use vary dramatically depending on whether you’re writing a literature review for a class paper or leading a Cochrane systematic review. You need to be clear on the distinction.

SYSTEMATIC REVIEWS

If you’re planning a systematic review, register your protocol first. PROSPERO (the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews) is a free database where you can register your protocol before you begin, helping prevent duplication and ensuring transparency.

A systematic review is the gold standard of evidence synthesis. It follows a pre-specified protocol, uses explicit and reproducible search strategies across multiple databases, applies predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria, critically appraises the quality of included studies, and synthesizes findings using rigorous methods (sometimes including meta-analysis).

Systematic reviews are hard. They typically take 12-24 months, require a team of at least two reviewers (to reduce bias in screening and extraction), and demand documentation of every decision. The Cochrane Collaboration and Campbell Collaboration produce systematic reviews that follow strict methodological standards and are recognized worldwide as authoritative sources of evidence.

In a hurry? Rapid reviews compress the systematic review process from 12-24 months to 12 weeks or less—essential during health emergencies when decisions can’t wait (Langlois et al., 2019).

When do you need a systematic review? When you’re making claims about “what the evidence shows” on a clinical or policy question. When you’re informing guidelines. When you need to be comprehensive and transparent about how you identified, selected, and synthesized evidence.

SCOPING REVIEWS

Read an example of a scoping review of TB infection control and prevention by Zwama and colleagues.

A scoping review maps the existing literature on a topic to identify the types of evidence available, clarify concepts, and identify knowledge gaps. Unlike systematic reviews, scoping reviews don’t typically assess the quality of included studies or synthesize findings to answer a specific effectiveness question.

Scoping reviews are useful when you’re exploring a new area, when the literature is diverse and heterogeneous, or when you want to understand the “lay of the land” before designing a more focused systematic review. They follow structured methods (the PRISMA-ScR guidelines provide a reporting framework), but they’re less rigid than systematic reviews.

NARRATIVE REVIEWS

Other synthesis approaches include meta-ethnography (synthesizing qualitative studies to generate new theory), realist reviews (testing what works, for whom, and why), and umbrella reviews (synthesizing existing systematic reviews).

A narrative review (sometimes called a “literature review” or “traditional review”) synthesizes and summarizes literature on a topic without following the strict protocols of a systematic review. The author selects sources based on relevance and expertise, and the synthesis is often more interpretive and thematic.

Narrative reviews are appropriate for providing background and context in a thesis introduction, identifying themes and debates in a field, offering expert perspective on a topic, and educational purposes.

The danger with narrative reviews is cherry-picking: selecting only evidence that supports your argument while ignoring contradictory findings. Good narrative reviews are transparent about their limitations and acknowledge they don’t claim to be comprehensive.

WHICH REVIEW IS FOR YOU?

Stop and ask yourself: What review type fits your current project? If you’re unsure, err on the side of more structure—you can always scale back, but it’s hard to add rigor retroactively.

| Your Goal | Review Type |

|---|---|

| Inform clinical guidelines | Systematic |

| Map a new field | Scoping |

| Provide context in a thesis | Narrative |

| Urgent policy decision | Rapid |

4.2 Start with the Best Available Evidence

Before you begin building complex search strings, check whether someone has already done the work. If a high-quality systematic review exists on your topic, start there. Why wade through hundreds of primary studies when someone has already identified, appraised, and synthesized them for you?

Trisha Greenhalgh, in her classic text on evidence-based medicine, offers this wisdom: “Always start at the top of the evidence pyramid. If someone has already synthesized the evidence, begin there.”

Read Greenhalgh’s original BMJ papers that became, How to Read a Paper.

THE EVIDENCE HIERARCHY (AND ITS LIMITS)

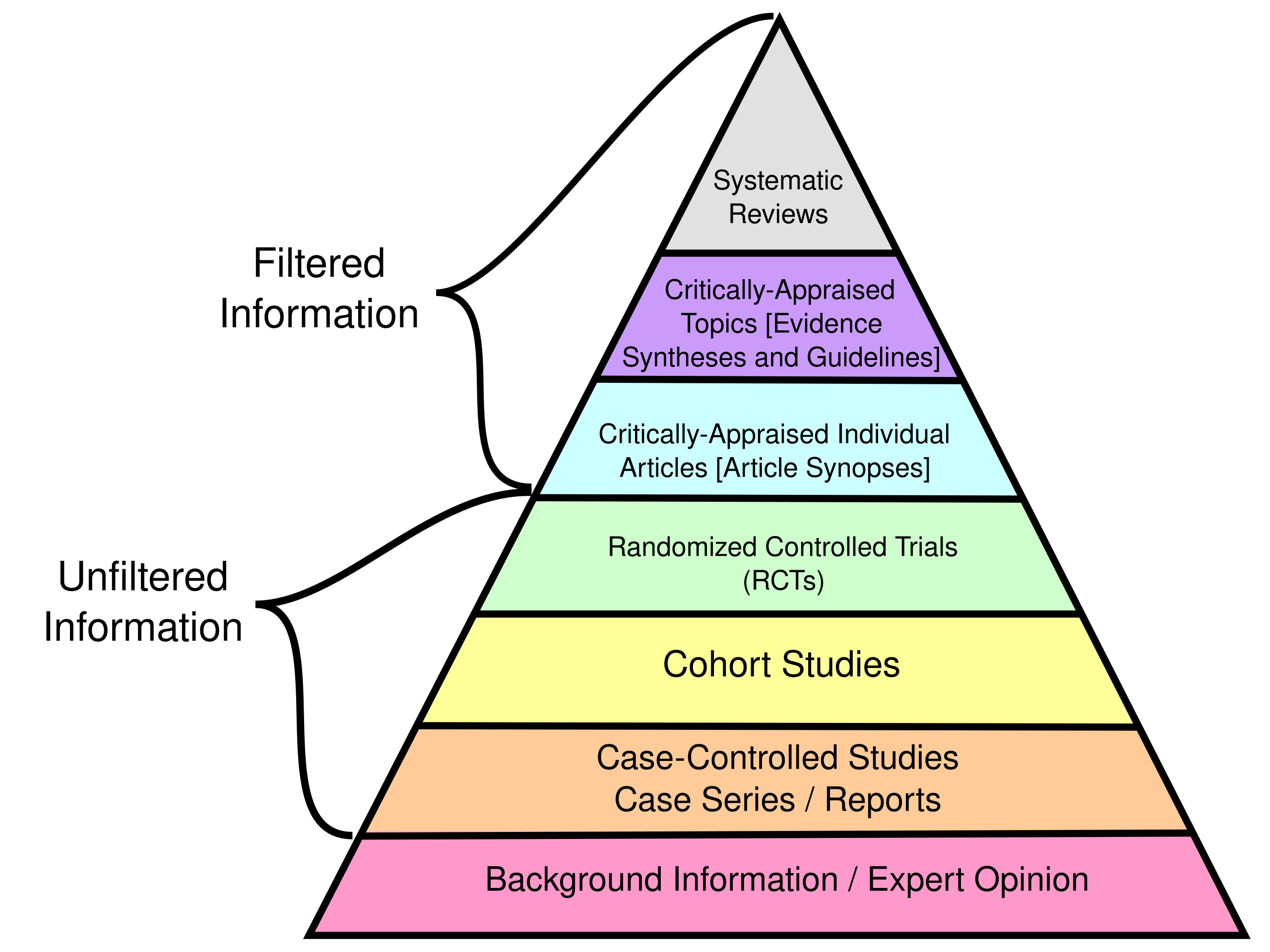

Evidence pyramid. Source: CFCF (2015). ghr.link/evi.

You’ve probably seen versions of the “evidence pyramid” with systematic reviews and meta-analyses at the top, followed by randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, case-control studies, case series, and expert opinion at the bottom. The idea is that higher levels represent more reliable evidence because they’re less susceptible to bias.

A poorly conducted randomized controlled trial does not necessarily provide better evidence than a rigorous case-control study. The details matter, not just the labels.

This hierarchy is useful as a starting point. But don’t take it too literally.

Here’s why: the best evidence for your specific question depends on your specific question. If you’re asking about the average effect of an intervention across populations, a systematic review of RCTs might be ideal. But if you’re asking how to implement that intervention in your specific context, a qualitative study from a similar setting might be more informative than a meta-analysis of trials from high-income countries.

MINING EXISTING REVIEWS

When you find a relevant systematic review, you have in your hands a roadmap to the literature. Look at the reference list—it’s a curated bibliography of relevant primary studies. Check when the review was conducted and search for newer studies that might have been published since. Google Scholar makes this easy with the “Cited by” feature. Keep up this approach with every high quality study you find and you’ll have a good sense of the literature on your topic.

4.3 Quick and Dirty Searches for Early Exploration

Sometimes you need to get oriented quickly. You’re brainstorming a new project, checking whether an idea is feasible, or trying to understand what literature exists before committing to a formal review. This is where “quick and dirty” searching comes in.

I use that term deliberately. These are not rigorous, comprehensive searches. They’re exploratory—designed to give you a sense of the landscape, not a complete map of it.

The goal of exploratory searching is to answer questions like:

- Has anyone studied this topic before?

- What terminology do researchers use?

- Who are the key authors in this area?

- What journals publish on this topic?

- What are the main debates or controversies?

- Where are the obvious gaps?

You’re not trying to find everything. You’re trying to learn enough to decide whether to proceed and, if so, how to structure a more rigorous search.

GOOGLE SCHOLAR: YOUR FRENEMY

Google Scholar is remarkably useful for exploration. It indexes broadly, includes grey literature and books that PubMed misses, and its “Cited by” and “Related articles” features are powerful tools for discovering relevant literature.

Here’s how to use it effectively:

Start broad, then narrow. Begin with your topic in plain language. See what comes up. What terms do authors use? What journals publish on this topic? What names keep appearing?

Use the “Cited by” feature. Found a seminal paper? Click “Cited by” to see everything that’s cited it since. This is gold for finding recent work that builds on foundational studies. A foundational paper with 500 citations essentially provides a curated reading list of the field’s development.

Use “Related articles.” Google’s algorithm identifies papers similar to one you’ve found. This can surface relevant work you’d never have found through keyword searching alone. I’ve found papers through this feature that used completely different terminology than I was searching for.

Check author profiles. Found a prolific researcher in your area? Look at their Google Scholar profile to see their other work. Often researchers work on related topics across multiple papers, and finding one good author can lead you to a body of relevant work.

But beware. Google Scholar doesn’t tell you what it’s searching, doesn’t use controlled vocabulary, and may include predatory journals in the results alongside legitimate ones. It’s a discovery tool, not a comprehensive search tool. Never rely on it alone for a formal review.

AI-ASSISTED SEARCH DISCOVERY TOOLS

AI tools are changing how researchers discover literature—and creating new ways to get into trouble. Used wisely, they can accelerate discovery. Used carelessly, they’ll lead you to cite papers that don’t exist.

What’s available: Tools like Elicit, Consensus, and Scite are designed specifically for research discovery. They let you ask questions in natural language and return relevant papers with AI-generated summaries. General-purpose tools like ChatGPT and Perplexity can also help you explore topics, though they weren’t built for systematic literature work.

The AI landscape is evolving rapidly. By the time you read this, new tools will exist and some mentioned here may have changed significantly. The principles matter more than the specific tools.

What they’re good for:

- Rapid orientation: Ask “What are the main approaches to treating severe acute malnutrition?” and get a structured overview faster than hours of reading.

- Finding connections: AI can surface papers that use different terminology than you’d think to search for.

- Summarizing across papers: Some tools synthesize findings across multiple studies, helping you see patterns.

- Generating search terms: Stuck on what to search? Ask an AI to suggest keywords, MeSH terms, or related concepts.

Why they’re dangerous:

- Not comprehensive: No AI tool searches all databases systematically. They’re discovery tools, not replacements for proper database searching.

- Inaccurate: AI tools can and do hallucinate citations—inventing plausible-sounding papers that don’t exist. Never cite a paper you found through AI without verifying it exists and says what the AI claimed.

- May not be recent: Training data has cutoffs. The newest literature may not be indexed.

- Not transparent: Unlike database searches, you can’t fully document what an AI searched or why it returned certain results—a problem for reproducible reviews.

Best practices:

- Verify everything. If an AI suggests a paper, find it in PubMed or Google Scholar and read it yourself. If you can’t find it, it may not exist.

- Use AI for discovery, databases for rigor. Let AI help you explore and generate ideas, then build proper searches in PubMed, Embase, and other databases.

- Document your process. Note which AI tools you used and how, even if you can’t fully reproduce AI outputs.

- Don’t trust summaries. AI summaries of papers can miss nuance, misstate findings, or reflect the AI’s training biases rather than what the paper actually says.

- Stay current. These tools improve rapidly. What’s unreliable today may be better tomorrow—and vice versa.

The researchers who will use these tools most effectively are those who understand both their power and their limitations. AI (probably) won’t replace careful scholarship, but it can make careful scholars more efficient. Be quick, not dirty.

KNOWING WHEN TO STOP

Exploratory searching can become a rabbit hole. You find one interesting paper, which leads to five more, which lead to twenty more, and suddenly you’ve spent three days reading and haven’t written a word.

Here are signs you’ve searched enough for exploratory purposes:

- Redundancy: You keep finding the same papers cited repeatedly, or new searches return mostly papers you’ve already seen.

- Conceptual clarity: You can articulate the main debates, gaps, and approaches in the field.

It’s important to accept that science is iterative. You’ll search, read, and think on repeat.

4.4 Systematic Searching

When do you need to be systematic? When your goal is to find all the relevant evidence on a question—not just enough to orient yourself or support an argument, but everything that exists. This is the foundation of a systematic review: a comprehensive, unbiased synthesis of what the research actually shows.

Systematic reviews answer questions like: “Does this intervention work? (and to what extent?)” “What does the totality of evidence suggest?” “Where are the gaps?” To answer these fairly, you can’t cherry-pick convenient studies. You need to surface all the knowledge—including studies that are harder to find, written in other languages, published in obscure journals, or sitting in grey literature repositories.

Publication bias means positive findings are more likely to be published. If your search doesn’t work hard to find unpublished and grey literature, you’ll overestimate intervention effects.

This matters because incomplete searching biases your conclusions. The studies you miss are often systematically different from the ones you find easily—they may have null or negative results, come from underrepresented regions, or challenge dominant narratives.

AI is quickly getting good at screening articles and extracting data, but full automation of the process is not possible yet. For now, you need to keep reading this section.

The good news: systematic searching is a learnable skill with clear steps. The bad news: it takes time, and there are few shortcuts that don’t compromise quality.

Buckle up, because the systematic review timeline is measured in months and years, not days and weeks.

STEP 0: BUILD A TEAM

Systematic reviews are a team sport. They are a lot of work to complete, and you need a variety of voices to be a check on the process.

If you’re Danny Ocean putting together your crack team, your first pick-up should probably be a librarian. Research librarians are trained in systematic search methods and know database quirks you’ve never heard of. Many universities offer librarian consultations specifically for systematic reviews.

You’ll also need content experts who understand the conditions, interventions, and exposures; methodological experts who can help with critical appraisal; and eager teammates willing to screen records and extract data. If your systematic review will include a quantitative technique called a meta-analysis, you’ll need someone to lead this work.

STEP 1: FORMULATE A CLEAR QUESTION

Your starting point is a well-formulated question. Your question should be specific enough to search but broad enough to capture relevant evidence.

Too broad: “How can we improve health in Africa?”

Too narrow: “What is the effect of the ASHA program on infant vaccination rates in rural Uttar Pradesh between 2015-2018?”

Just right: “What is the effectiveness of community health worker programs for improving childhood vaccination coverage in low-income countries?”

A good strategy for developing a well-formulated question is to use a framework like PICO (see Chapter 3):

- Population: Who are you studying?

- Intervention/Exposure: What intervention or exposure are you interested in?

- Comparison: What is the comparison (if any)?

- Outcome: What outcomes matter?

STEP 2: DEVELOP A SEARCH STRATEGY

With your question formulated and team assembled, it’s time to build the search strategy that will actually find the evidence. A search strategy has two main components: search terms (the words you’ll search for) and database queries (the structured searches you’ll run in specific databases). Let’s tackle each in turn.

Identifying Search Terms

Break your question into concepts and identify all the ways those concepts might be expressed in the literature. For each concept, generate:

- Primary terms (the obvious words researchers use)

- Synonyms (alternative words for the same concept)

- Related terms (broader or narrower concepts that might capture relevant literature)

- British vs. American spellings (organisation/organization, paediatric/pediatric)

- Abbreviations and acronyms (CHW, VHW, ASHA)

- Historical terms that might appear in older literature (“barefoot doctor”)

Building a comprehensive term list is tedious but essential. Missing a key synonym means missing studies that use that term. Your librarian can help identify terms you haven’t thought of.

For “community health workers,” your list might include: community health worker, community health aide, village health worker, lay health worker, health extension worker, community health volunteer, CHW, VHW, barefoot doctor, promotora, ASHA (in India), health surveillance assistant (in Malawi)…

Do this for each concept in your PICO question. You’ll end up with multiple lists of terms that you’ll combine using Boolean logic.

Using Controlled Vocabulary

Major databases use controlled vocabulary—standardized terms assigned to articles by indexers. In PubMed, these are called MeSH (Medical Subject Headings). In Embase, they’re called Emtree terms. CINAHL has its own headings.

Find MeSH terms using the MeSH database.

Controlled vocabulary thesauruses are helpful because there are many ways to refer to the same phenomenon. For instance, the MeSH term for “breast cancer” is “breast neoplasm.” A search for “breast neoplasm” in PubMed actually searches more than 30 entry terms, such as “Tumors, Breast”, “Mammary Neoplasms, Human”, and “Carcinoma, Human Mammary”.

A sophisticated search uses both keyword searching (to catch new articles not yet indexed) AND controlled vocabulary (to comprehensively capture indexed literature).

Building Boolean Search Strings

Sensitivity vs. specificity: A sensitive search casts a wide net, finding all relevant articles but also many irrelevant ones (false positives). A specific search is targeted, missing some relevant articles (false negatives) but returning mostly good matches. For systematic reviews, prioritize sensitivity—missing studies is worse than screening extras.

Once you have your terms, you need to combine them into a search query using Boolean operators AND, OR, and NOT.

- OR expands your search (finds articles with any of the terms): “community health worker” OR “village health worker”

- AND narrows your search (finds articles with all of the terms): “community health worker” AND “malaria”

- NOT excludes terms (use cautiously—you might exclude relevant articles): “malaria” NOT “vivax”

Use parentheses to group terms and control how the Boolean operators apply:

("community health worker" OR "village health worker"

OR "lay health worker")

AND

("child health" OR "child mortality"

OR "under-five mortality")

AND

("Africa" OR "sub-Saharan Africa"

OR [list of country names])Customize Search Strings for Each Database

For systematic reviews, you should also search:

- Trial registries (ClinicalTrials.gov, WHO ICTRP)

- Conference proceedings

- Grey literature sources (more on this later)

- Reference lists of included studies

No single database indexes everything. For health research, a minimum search typically includes:

- PubMed/MEDLINE: Biomedical literature, particularly clinical research

- Embase: Stronger in pharmacology and non-US literature

- CINAHL: Nursing and allied health literature

- Global Health Database: International public health literature

- Regional databases: LILACS for Latin America, African Index Medicus, Western Pacific Region Index Medicus

One of the practical headaches of systematic searching is that each database uses slightly different syntax. A search string that works perfectly in PubMed will fail in Embase.

Common differences include:

- Truncation symbols: PubMed uses *, Ovid uses $, some databases use ?

- Field codes: PubMed uses [tiab] for title/abstract, Ovid uses .ti,ab.

- Phrase searching: Some databases require quotes, others use proximity operators

- Boolean operators: Some databases require all caps (AND, OR), others accept lowercase

This means you can’t simply copy and paste your search between databases. You need to translate your search strategy for each platform.

Supplemental Searches

Database searching alone won’t find everything. For comprehensive systematic reviews, you’ll also need to:

- Search trial registries: ClinicalTrials.gov and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) list registered trials, many of which are never published

- Check reference lists: “Backward citation searching” finds older relevant studies; “forward citation searching” (via Google Scholar’s “Cited by”) finds newer ones

- Search grey literature: WHO IRIS, UN agency repositories, ministry of health websites, and organizational reports often contain evidence that never appears in indexed journals—particularly important in global health where much implementation evidence lives outside academic publishing

- Contact experts: Email researchers and program managers in your area asking about unpublished work, ongoing studies, or reports you might have missed. This “snowball” approach often uncovers documents you’d never find through searching alone

STEP 3: DEFINE INCLUSION AND EXCLUSION CRITERIA

Write your criteria before searching, not after. Changing criteria after seeing results introduces bias—you might unconsciously exclude studies with inconvenient findings.

Before searching, specify exactly which studies you’ll include and exclude. Clear criteria prevent bias—you decide what’s in and out BEFORE you see the results, not after.

Inclusion criteria define what a study must have to be considered:

- Population: Who must the study include? (e.g., pregnant women, children under 5)

- Intervention/Exposure: What intervention or exposure must be studied?

- Comparator: What comparison is required, if any?

- Outcomes: What outcomes must be measured?

- Study design: Which designs will you accept? (RCTs only? Observational studies too?)

- Time frame: Any date restrictions on publication?

- Language: Will you include non-English studies?

- Setting: Any geographic or contextual requirements?

Exclusion criteria specify what disqualifies a study. Common exclusions include conference abstracts without full data, studies in languages your team can’t read, or study designs prone to bias for your question.

STEP 4: REGISTER A PROTOCOL

PROSPERO (the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews) is free and widely used for health-related systematic reviews.

A protocol is a detailed plan that specifies your methods before you see the results. It includes your research question, eligibility criteria, search strategy, screening procedures, data extraction plans, quality assessment approach, and analysis methods.

Why register? Several reasons:

Transparency: Registration creates a public record of what you planned to do before you knew what you’d find. This protects against accusations of cherry-picking or post-hoc changes to methods.

Preventing duplication: Other researchers can see your registered protocol and avoid duplicating your work. You can also check PROSPERO before starting to see if someone else is already working on your question.

Methodological discipline: The process of writing a protocol forces you to think through your methods carefully. Decisions made in advance are more defensible than decisions made after seeing results.

Journal requirements: Many journals now require PROSPERO registration for systematic reviews. Some funders require it too. Better to register upfront than scramble to explain why you didn’t.

Your protocol should include:

- Your research question

- Eligibility criteria (what study designs, populations, interventions, and outcomes will you include?)

- Information sources (which databases and other sources will you search?)

- Search strategy (your full search strings for at least one database)

- Study selection process (how many reviewers, how will disagreements be resolved?)

- Data extraction process (what information will you extract, using what forms?)

- Quality assessment (what tool will you use to assess risk of bias?)

- Analysis plan (narrative synthesis, meta-analysis, or both?)

PROSPERO allows you to update your registration if you need to make changes, but you must document and justify any deviations from your original protocol.

STEP 5: COLLECT SEARCH RESULTS

Now comes the satisfying part: running your searches and watching the results pile up. But “satisfying” comes with a warning—this step requires meticulous documentation, or you’ll regret it later.

Running and Documenting Searches

Run your search in each database, adapting the syntax as needed. For each database, document:

- Database name and platform (e.g., “Embase via Ovid”)

- Date of search

- Exact search string (copy and paste directly from the database)

- Any limits applied (date range, language, publication type)

- Number of results retrieved

Save your search histories within each database when possible. Most databases let you save searches for later re-running, which is useful if you need to update your review.

This documentation is essential for the methods section of your paper, for PRISMA reporting, and for defending your work against criticism. Someone else should be able to run your exact search and get the same results (or very similar—databases update continuously).

Managing References with a Reference Manager

For larger reviews, consider using dedicated systematic review software like Covidence.

You’ll be dealing with hundreds or thousands of citations. Trying to manage these in a spreadsheet or Word document is a recipe for chaos. Use a reference manager.

Zotero is my recommendation—it’s free, open-source, and works well for systematic reviews. But Mendeley, EndNote, or other managers work too. The key is picking one and using it consistently.

Import your search results directly from each database into your reference manager. Most databases offer export options (RIS, BibTeX, or direct export to specific managers). Keep search results from different databases in separate collections initially—you’ll need these numbers for your PRISMA flow diagram.

Deduplication

When you search multiple databases, you’ll retrieve the same citations multiple times. A paper indexed in both PubMed and Embase will appear in both search results.

Reference managers can identify duplicates, but automatic deduplication isn’t perfect. Common problems include:

- Slight differences in author names or titles

- Different versions (preprint vs. published article)

- Erratum notices counted as separate records

Plan to spend time manually checking potential duplicates. Document how many duplicates you removed—this is part of your PRISMA flow diagram.

STEP 6: SCREENING RESULTS

You’ve collected your search results—perhaps 2000 citations, perhaps 10,000. Now you need to identify which ones actually meet your eligibility criteria. This happens in two stages: title/abstract screening and full-text screening.

Screening Models and Inter-Rater Reliability

The gold standard is dual independent screening: two reviewers independently screen every citation, then compare decisions and resolve disagreements through discussion or a third reviewer. This catches errors and inconsistencies but doubles the workload—a real constraint when you’re facing thousands of citations.

Alternatives exist that divide the work. Once reviewers demonstrate they apply eligibility criteria consistently, some teams split the remaining citations between reviewers, with each screening independent batches. A hybrid approach has reviewers screen most citations independently but periodically screen random subsets in duplicate to monitor ongoing agreement.

Cohen’s kappa measures inter-rater reliability. A kappa of 0.6-0.8 indicates substantial agreement; above 0.8 indicates almost perfect agreement.

If you choose an approach that divides citations between reviewers, you must first establish inter-rater reliability. Why? Because screening decisions are subjective. Reviewers bring different interpretations of eligibility criteria, different thresholds for “maybe,” and different levels of attention depending on fatigue. Without verification, you might have one reviewer applying stricter criteria than another—and you’d never know.

Before dividing the work, pilot your process:

- Both reviewers screen the same 50-100 citations independently

- Compare decisions and calculate agreement (Cohen’s kappa)

- Discuss disagreements to clarify eligibility criteria

- Refine your screening guide as needed

- Repeat until agreement is acceptable (typically kappa > 0.8)

Only after establishing strong agreement should you divide the remaining citations. Document your approach and inter-rater reliability in your methods section.

Title and Abstract Screening

In the first stage, you review titles and abstracts to identify citations that are potentially relevant. You’re not making final inclusion decisions yet—you’re identifying which citations deserve a closer look.

Be inclusive during title/abstract screening. When in doubt, keep it in. It’s better to retrieve and reject a full text than to accidentally exclude a relevant study based on an ambiguous abstract.

Develop clear screening criteria based on your eligibility criteria. For each citation, ask: Based on the title and abstract alone, is this study potentially about my population, intervention, comparison, and outcome? If the answer is clearly “no,” exclude it. If the answer is “yes” or “maybe,” include it for full-text review.

This stage goes quickly once you get into a rhythm—experienced reviewers can screen 100+ abstracts per hour. But speed shouldn’t compromise consistency.

Full-Text Screening

Citations that pass title/abstract screening move to full-text review. Now you retrieve the actual articles and apply your full eligibility criteria.

This stage is slower—you’re reading methods sections, checking study populations, verifying outcome definitions. It’s also where you’ll exclude the most studies, often for reasons that weren’t clear from abstracts.

Document your exclusion reasons at this stage. Common reasons include:

- Wrong population

- Wrong intervention

- Wrong comparator

- Wrong outcome

- Wrong study design

- Duplicate publication

- Unable to obtain full text

You’ll report the number excluded for each reason in your PRISMA flow diagram. Keep a spreadsheet or use your systematic review software to track these decisions.

Access barriers shape who can conduct research. Options for obtaining articles include: institutional access through your library; HINARI (free/low-cost access for institutions in low- and lower-middle-income countries); open access journals indexed in DOAJ; preprint servers like medRxiv and bioRxiv; author manuscripts in repositories like PubMed Central; and simply emailing authors—most researchers are happy to share their work.

STEP 7: EXTRACTING DATA

Studies that survive full-text screening become your included studies. Now you need to systematically extract information from each one into a standardized format.

Developing a Data Extraction Form

You might do this in a shared Excel or Google Sheets file, or maybe your team will use systematic review software.

Before extracting anything, develop a data extraction form—a template that specifies exactly what information you’ll collect from each study. This ensures consistency across studies and reviewers.

Your extraction form typically includes:

Study characteristics:

- Authors, year, title, journal

- Country/setting

- Study design

- Sample size

- Funding source

Population characteristics:

- Eligibility criteria

- Demographics (age, sex, socioeconomic status)

- Health status

Intervention details:

- What was the intervention?

- Who delivered it?

- What was the intensity, duration, frequency?

- What was the comparator?

Outcomes:

- How was the outcome defined and measured?

- Timing of outcome assessment

- Results (effect sizes, confidence intervals, p-values)

Quality indicators:

- Information needed for risk of bias assessment

Pilot your extraction form on 3-5 studies before extracting from all included studies. You’ll almost certainly discover items that are unclear, missing, or unnecessary.

The Extraction Process

Like screening, data extraction benefits from dual independent extraction. Two reviewers extract data from each study, then compare and reconcile differences. This catches errors and forces explicit decisions about how to handle ambiguities.

Some practical tips:

- Extract data into a spreadsheet or database, not into prose

- When information is missing or unclear, note this explicitly rather than guessing

- If a study reports multiple outcomes or time points, extract all relevant data

- Contact study authors if critical information is missing (though response rates vary)

Extraction is tedious but important. Errors at this stage propagate through your analysis. Take breaks, double-check numbers, and reconcile discrepancies carefully.

STEP 8: CRITICAL APPRAISAL

Not all studies are created equal. A well-designed randomized trial provides stronger evidence than a poorly designed observational study. Critical appraisal (also called risk of bias assessment) evaluates the methodological quality of each included study.

Why Critical Appraisal Matters

Imagine two studies of the same intervention reach opposite conclusions. How do you interpret this? Critical appraisal helps you understand whether the discrepancy reflects true heterogeneity in effects or methodological differences that make one study more trustworthy than the other.

Critical appraisal also informs your synthesis. You might decide to:

- Conduct sensitivity analyses excluding high-risk-of-bias studies

- Weight studies by quality in your synthesis

- Present results stratified by risk of bias

- Downgrade your confidence in conclusions if most evidence is low quality

Choosing an Appraisal Tool

Different study designs require different appraisal tools:

- Cochrane Risk of Bias tool (RoB 2): For randomized trials

- ROBINS-I: For non-randomized intervention studies

- Newcastle-Ottawa Scale: For cohort and case-control studies

- CASP checklists: For various study designs including qualitative

- JBI critical appraisal tools: Comprehensive suite for different designs

- GRADE: For rating certainty of evidence across a body of studies

Quality assessment tools assess methodological quality, not reporting quality. A well-reported but poorly designed study is still low quality. A well-designed but poorly reported study might be high quality—you just can’t tell.

Most tools assess key domains that affect bias:

- Selection bias: Were participants selected in a way that could bias results?

- Performance bias: Were there systematic differences in care between groups?

- Detection bias: Could outcome assessment have been influenced by knowledge of group assignment?

- Attrition bias: Were there systematic differences in withdrawals?

- Reporting bias: Were all intended outcomes reported?

Conducting Critical Appraisal

Like screening and extraction, critical appraisal should be done independently by two reviewers. Each reviewer rates each study on each domain, then reviewers compare and reconcile differences.

Present your critical appraisal results in your review—typically as a summary table or figure showing risk of bias judgments across studies and domains. This transparency helps readers interpret your findings.

STEP 9: META-ANALYSIS (OPTIONAL)

Meta-analysis is a statistical technique for combining results across studies to generate a pooled estimate of effect. It’s the “meta” in systematic review—synthesizing quantitative findings across the body of evidence.

But meta-analysis isn’t always appropriate or possible. This step is optional, and knowing when not to do it is as important as knowing how.

When Meta-Analysis Makes Sense

Meta-analysis is appropriate when:

- You have multiple studies measuring the same outcome

- Studies are similar enough in population, intervention, and design to meaningfully combine

- Effect estimates and variance can be extracted or calculated

- The resulting pooled estimate would answer a meaningful question

When to Avoid Meta-Analysis

Don’t force a meta-analysis when:

Studies are too heterogeneous: If studies differ substantially in populations, interventions, or outcomes, a pooled estimate may be meaningless or misleading.

Too few studies: With only 2-3 studies, meta-analysis provides little benefit and can give false precision.

Data quality is poor: Garbage in, garbage out. Meta-analyzing low-quality studies produces a precise but potentially biased estimate.

Effect measures aren’t compatible: Combining odds ratios with risk ratios with hazard ratios requires assumptions that may not hold.

A narrative synthesis can be more informative than a forced meta-analysis. Describing patterns, explaining heterogeneity, and acknowledging uncertainty sometimes serves readers better than a forest plot.

Basic Meta-Analysis Concepts

If meta-analysis is appropriate, you’ll need to understand several key concepts:

Effect measures: The standardized way of expressing results (risk ratio, odds ratio, mean difference, standardized mean difference). All studies must use the same measure or be converted.

Fixed vs. random effects models: Fixed-effect models assume all studies estimate the same underlying effect. Random-effects models assume effects vary across studies and estimate the average effect and the heterogeneity.

Heterogeneity: The extent to which results vary across studies beyond what chance would predict. Measured by I² (percentage of variability due to heterogeneity) and Q statistic.

Forest plots: The standard visualization showing each study’s effect estimate and confidence interval, plus the pooled estimate. (For guidance on interpreting forest plots, see Chapter 5.)

Publication bias assessment: Methods like funnel plots and statistical tests to detect whether published studies systematically differ from unpublished ones.

Meta-analysis is a skill that takes training to do well. If you’re planning to include one, consider involving a statistician or epidemiologist with meta-analysis experience on your team.

Individual Participant Data Meta-Analysis

Standard meta-analysis works with aggregate data—the summary statistics reported in each study (means, proportions, effect estimates). But there’s a more powerful alternative: individual participant data (IPD) meta-analysis, which obtains the raw, participant-level data from each study and reanalyzes it.

Why go to this trouble? IPD meta-analysis offers several advantages. You can conduct subgroup analyses that weren’t reported in the original publications—examining whether treatment effects differ by age, sex, disease severity, or other characteristics. You can standardize outcome definitions and analysis methods across studies, reducing heterogeneity that stems from methodological differences rather than true variation. You can handle missing data more appropriately and check data quality directly. And you can examine time-to-event outcomes more precisely than aggregate survival curves allow.

The challenges are substantial. You need to contact original study authors and convince them to share their data—a process that can take months and often fails for older studies or when investigators have moved on. You need infrastructure to securely receive, clean, and harmonize datasets that were collected and coded differently. You need statistical expertise beyond standard meta-analysis. And the whole process takes considerably more time and resources than aggregate data meta-analysis.

When is IPD meta-analysis worth pursuing? Consider it when your primary research question involves subgroup effects that aren’t consistently reported, when you need to standardize outcome definitions across studies, or when individual studies are too small to detect effects in key subgroups but pooled IPD would have adequate power. Large collaborative groups—like the Cochrane IPD Meta-analysis Methods Group—have developed methods and infrastructure to support these efforts in specific clinical areas.

STEP 10: WRITING A SUMMARY

Your systematic review culminates in a written report that synthesizes what you found. This isn’t just a formality—it’s how your work contributes to knowledge and informs decisions.

The PRISMA Statement

The PRISMA Statement (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) provides a checklist and flow diagram for reporting systematic reviews. Following PRISMA ensures you report all essential information and makes your review easier to use and replicate.

Key components include:

- Title: Identify the report as a systematic review (and meta-analysis if applicable)

- Abstract: Structured summary of objectives, methods, results, and conclusions

- Introduction: Rationale for the review and explicit research questions

- Methods: Eligibility criteria, information sources, search strategy, selection process, data extraction, risk of bias assessment, synthesis methods

- Results: Study selection (PRISMA flow diagram), study characteristics, risk of bias, results of syntheses

- Discussion: Summary of evidence, limitations, conclusions

The PRISMA 2020 statement updated earlier versions with new reporting items. Check prisma-statement.org for the current checklist and explanation document.

The PRISMA Flow Diagram

Every systematic review needs a flow diagram showing how you went from initial search results to final included studies. The diagram shows:

- Records identified from each source

- Records after deduplication

- Records screened (title/abstract)

- Records excluded at screening

- Full-text articles assessed

- Full-text articles excluded (with reasons)

- Studies included in the review

- Studies included in meta-analysis (if applicable)

This transparency lets readers assess the comprehensiveness of your search and understand how you arrived at your included studies.

Narrative Synthesis

Even if you conduct a meta-analysis, you’ll write narrative text synthesizing your findings. This includes:

- Summarizing characteristics of included studies

- Describing results across studies, noting patterns and inconsistencies

- Explaining heterogeneity when present

- Linking findings to risk of bias assessments

- Contextualizing results within the broader literature

Good narrative synthesis tells a story—not a biased story that cherry-picks convenient findings, but a balanced story that helps readers understand what the evidence shows, where it’s strong, and where uncertainty remains.

Stating Limitations

Every systematic review has limitations. Common ones include:

- Searches may have missed relevant studies (language restrictions, grey literature gaps)

- Included studies may have methodological limitations

- Heterogeneity may limit ability to draw conclusions

- Publication bias may affect findings

- The evidence may not generalize to all settings

Be honest about limitations. Readers and decision-makers need to know how much confidence to place in your conclusions.

Drawing Conclusions

Your conclusions should flow directly from your findings. Avoid overstating—if the evidence is weak or inconsistent, say so. Recommendations for practice and research should be specific and justified by your findings.

Consider your audience. Policymakers need clear, actionable messages. Researchers need to understand the gaps your review identified. Practitioners need to know how findings apply to their context.

A WORKED EXAMPLE: THE COCHRANE REVIEW ON MALARIA PREVENTION IN PREGNANCY

Let me walk you through how all of these steps come together using a real systematic review: the Cochrane review by Radeva-Petrova and colleagues on “Drugs for preventing malaria in pregnant women in endemic areas” (Radeva-Petrova et al., 2014). This review exemplifies rigorous systematic review methods and illustrates how the concepts translate into practice.

Step 1: Their PICO Question

The review team formulated a clear question using the PICO framework:

- Population: Pregnant women of any gravidity living in malaria-endemic areas

- Intervention: Any antimalarial drug chemoprevention regimen

- Comparison: Placebo or no intervention

- Outcomes: Maternal outcomes (mortality, severe anaemia, parasitaemia) and infant outcomes (mortality, birthweight, placental parasitaemia)

In malaria-endemic areas, what are the effects of malaria chemoprevention compared to no chemoprevention on maternal and infant health outcomes?

Notice how they kept the question broad enough to capture all relevant evidence while being specific enough to be answerable. They didn’t restrict to a single drug or outcome—they wanted comprehensive evidence on chemoprevention as a strategy.

Step 2: Their Search Strategy

The Cochrane team searched multiple databases using terms for each PICO concept. Their search covered:

- Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group Specialized Register

- CENTRAL (Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials)

- MEDLINE (1966 to June 2014)

- EMBASE (1974 to 2012)

- LILACS (1982 to 2012)

- Reference lists of identified trials

They also contacted researchers working in the field for unpublished data, confidential reports, and raw data—an important step for comprehensive searching that’s easy to overlook.

Step 3: Their Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The team specified clear eligibility criteria before searching:

- Include: Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi-RCTs of any antimalarial drug regimen for preventing malaria, compared to placebo or no intervention

- Include: Regimens that were known to be effective against malaria parasites at the time (even if now obsolete due to resistance)

- Exclude: Studies comparing different active drug regimens (these went into a separate review)

This illustrates an important principle: they included drugs no longer in use because those trials still inform our understanding of chemoprevention as a strategy. The question wasn’t “Does sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine work?” but “Does chemoprevention work?”

Step 4: Registering the Protocol

As a Cochrane review, the protocol was registered and published before the review was conducted. This pre-specification of methods protects against bias—the team couldn’t change their analysis approach after seeing the results.

Step 5: Collecting Results

Running their search across databases, the team retrieved:

- 181 records identified through database searching

- 2 additional records identified through other sources (reference lists, expert contacts)

- After removing 2 duplicates: 179 unique records to screen

Step 6: Screening

Two reviewers independently applied inclusion criteria. Their PRISMA flow shows:

Title and abstract screening:

- 179 records screened

- 126 records excluded (clearly not relevant based on title/abstract)

- 53 full-text articles retrieved for detailed assessment

Full-text screening:

- 53 full-text articles assessed for eligibility

- 31 articles excluded with documented reasons

- 17 trials included (described in 22 separate publications)

The 31 excluded articles each had a documented reason for exclusion—this transparency is essential for reproducibility and lets readers assess whether the exclusions were appropriate.

Step 7: Extracting Data

Using standardized forms, reviewers independently extracted:

- Study characteristics: Authors, year, country, setting, malaria transmission intensity

- Population: Sample size, parity (first pregnancy vs. multigravidae), HIV status where reported

- Intervention details: Drug (chloroquine, pyrimethamine, proguanil, pyrimethamine-dapsone, mefloquine, or sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine), dosing schedule (daily, weekly, or intermittent)

- Outcomes: Maternal mortality, severe anaemia, any anaemia, parasitaemia; infant mortality, birthweight, placental parasitaemia

The 17 included trials enrolled 14,481 pregnant women across Nigeria (3 trials), The Gambia (3), Kenya (3), Mozambique (2), Uganda (2), Cameroon (1), Burkina Faso (1), and Thailand (2), conducted between 1957 and 2008.

Step 8: Critical Appraisal

Using Cochrane’s Risk of Bias tool, the team assessed each trial. Their findings reveal a common pattern in older literature:

- 6 trials had adequate allocation concealment (low risk of selection bias)

- 4 trials were quasi-randomized (high risk of selection bias)

- 7 trials had unclear risk of selection bias

Only 6 of 17 trials met modern standards for preventing selection bias—yet excluding the weaker trials didn’t change the conclusions, strengthening confidence in the findings.

Step 9: Meta-Analysis

With multiple trials measuring similar outcomes, meta-analysis was appropriate. Key findings for women in their first or second pregnancy:

Maternal outcomes:

- Severe anaemia: RR 0.60 (95% CI 0.47 to 0.75)—chemoprevention reduced severe anaemia by 40% (high quality evidence)

- Antenatal parasitaemia: RR 0.39 (95% CI 0.26 to 0.58)—chemoprevention reduced parasitaemia by 61% (high quality evidence)

- Maternal mortality: Only 16 deaths across all trials—underpowered to detect an effect (very low quality evidence)

Infant outcomes:

- Mean birthweight: 93 grams higher with chemoprevention (95% CI 62 to 123) (moderate quality evidence)

- Low birthweight: RR 0.73 (95% CI 0.61 to 0.87)—27% reduction (moderate quality evidence)

- Placental parasitaemia: RR 0.54 (95% CI 0.43 to 0.69)—46% reduction (high quality evidence)

The review used GRADE to rate evidence quality, transparently communicating confidence in each finding.

Step 10: Writing the Summary

The PRISMA flow diagram documented the journey from 181 records to 17 included trials. The Summary of Findings tables presented key results in accessible format for decision-makers.

The team acknowledged limitations honestly: most evidence came from Africa, trials spanned five decades of changing drug resistance and healthcare contexts, and mortality outcomes were underpowered. They noted that benefits might be attenuated in settings with declining malaria transmission and improving antenatal care.

Their conclusion was appropriately cautious yet actionable: “Routine chemoprevention to prevent malaria and its consequences has been extensively tested in RCTs, with clinically important benefits on anaemia and parasitaemia in the mother, and on birthweight in infants.”

What This Example Teaches Us

This Cochrane review illustrates several key principles:

- Comprehensive searching matters: Five databases plus expert contacts and reference checking

- Pre-specification prevents bias: The protocol was registered before seeing results

- Transparency enables trust: Every excluded study was documented with reasons

- Quality assessment informs interpretation: Knowing most trials had bias concerns, but sensitivity analyses confirmed findings

- GRADE clarifies confidence: Distinguishing high-quality evidence (anaemia) from very low quality (mortality) helps users understand certainty

- Honest limitations strengthen credibility: Acknowledging what the evidence can and cannot tell us

4.5 Watch Out for Junk Science

Not everything that looks like science is good science. As you search the literature, you’ll encounter predatory journals, poorly conducted studies, and sometimes outright fraud. Developing a critical eye is essential—both for avoiding junk science in your own reviews and for protecting yourself from publishing in the wrong venues.

PREDATORY JOURNALS

Predatory journals mimic legitimate academic journals but exist primarily to collect publication fees without providing genuine peer review or editorial services. They look like real journals. They have official-sounding names. They send professional-looking emails. But behind the facade, there’s no real peer review, no editorial oversight, and no quality control.

Why do researchers publish in predatory journals? Sometimes they’re deceived—the journal seemed legitimate. Sometimes they’re desperate—facing pressure to publish and finding legitimate venues too slow or too competitive. Sometimes they’re complicit—seeking a quick publication for their CV without caring about quality. Researchers from LMICs are disproportionately targeted and publish in predatory journals at higher rates than their counterparts in high-income countries, partly because they see predatory journals as “low-hanging fruit” offering faster publication pathways (Sharma et al., 2023).

HOW PREDATORY JOURNALS TARGET RESEARCHERS

If you have an academic email address, you’ve probably received solicitations from predatory journals. The emails often flatter (“Dear Distinguished Professor”), claim to have seen your recent work (“We were impressed by your publication”), and urgently invite submission (“Special discount if you submit within 48 hours”).

These emails can be persuasive, especially for early-career researchers eager to build their publication records. The journals often have names that sound similar to legitimate journals (Journal of Medical Sciences vs. Journal of Medical Science), making it easy to confuse them with reputable venues.

Some predatory publishers have become sophisticated. They organize fake conferences, create fake impact metrics, and establish fake indexing services to lend credibility to their operations. The ecosystem of predatory publishing is now self-reinforcing: predatory journals cite each other to inflate citation counts, predatory conferences invite authors to present papers later published in predatory journals, and predatory indexing services include predatory journals to make them appear legitimate.

VERIFICATION STRATEGIES

Check DOAJ: The Directory of Open Access Journals only indexes journals meeting quality criteria. If an open access journal isn’t in DOAJ, investigate further.

Check indexing: Is the journal indexed in PubMed, Scopus, or Web of Science? Indexing isn’t a guarantee of quality, but lack of indexing in any major database is a warning sign.

Look up the publisher: Search for the publisher name plus “predatory” or “scam.” Check resources like Beall’s List (though it’s no longer actively updated) or Stop Predatory Journals.

Examine the editorial board: Are the editors real people with verifiable academic affiliations? Can you find their work in legitimate venues?

Read some published articles: Do they look professionally edited? Is the science plausible?

4.6 Closing Reflection

We’ve covered a lot of ground. From choosing your review type to building Boolean searches to avoiding predatory journals, searching the literature involves many skills that improve with practice. But I want to close with something that transcends technique.

Searching the literature is fundamentally an act of connecting with the collective knowledge of your field. When you search, you’re joining a conversation that stretches back decades (sometimes centuries) and spans the globe. You’re learning what questions others have asked, what they’ve found, and where they’ve hit dead ends. This is humbling. For any question you have, someone has probably thought about it before. Your contribution isn’t to reinvent everything from scratch but to build on what’s known, filling gaps and advancing understanding incrementally.

Searching the literature also reveals how a field thinks. The concepts that have MeSH terms, the journals that exist, the research questions that get funded—these reflect assumptions, priorities, and power structures. As global health researchers, we should notice whose voices appear in the literature and whose are absent. The gaps in the literature are as informative as the papers you find. They reveal where evidence is needed, where voices are missing, and where your contribution might be most valuable.

I encourage you to embrace searching not as a chore to complete but as a core scholarly practice to develop. The better you get at finding evidence, the better your research questions, the stronger your arguments, and the more impactful your contributions. The literature is out there. Go find it.